Adam N. Michel

Last week, the Cato Congressional Fellows discussed the history of radical tax reforms and examples of such reforms in practice.

This overview begins with a brief history of consumption tax reform proposals over the past half-century. It then turns to the Estonian tax system as a real-life model of a simple, flat income tax and describes how the Cato Tax Reform Plan helps policymakers move the US tax code toward one of these ideals. The second-to-last section reviews wealth taxes, another type of radical tax proposal, and the last section reviews significant tax changes between 1970 and the 2010s.

This blog is the third part of a four-part series based on notes from a Cato congressional fellowship series covering the US federal tax code. Part one is on Tax Code 101, and part two is on the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

This session was co-taught with Cato’s Chris Edwards.

Brief History of Major Tax Reform Efforts

In the first installment of this series—Tax Code 101—we discussed the differences between consumption and income tax bases. The popularity of flat-rate consumption taxes gained steam in the wake of repeated tax increases in the 1980s and 1990s, punctuated by President George H. W. Bush’s broken promise not to raise taxes.

In December 1981, economists Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka outlined their flat-tax proposal to fit individual tax returns on a postcard in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. The proposal paired a wage tax and a business cash flow tax to create a consumption tax base. It was later expanded into a book and became an animating feature in Republican politics.

The 1990s saw many competing flat-rate consumption tax proposals. House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R‑TX) and two-time presidential candidate Steve Forbes popularized versions of the Hall–Rabushka flat tax. Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Archer (R‑TX) promoted a national sales tax, which later became the Fair Tax proposal for a national retail sales tax. These and similar consumption tax plans, such as Sens. Sam Nunn (D‑GA) and Pete Domenici’s (R‑NM) USA Tax, were the subject of numerous congressional hearings and commissions.

Democrats shared the flat-tax fever. In addition to Nunn, Dick Gephardt (D‑MO), Leon Panetta (D‑CA), and Jerry Brown (California governor and presidential candidate) proposed versions of flat taxes.

In theory, each model of consumption tax—Flat Tax, Fair Tax, USA Tax—has different collection points but similar economic results, all ending with a similar tax base. However, some versions, such as the national sales tax, may require higher tax rates and necessitate repealing the Sixteenth Amendment to ensure the federal government does not end up levying taxes on income and sales, like in European countries where citizens pay significantly higher tax burdens.

Ultimately, a radical overhaul to the tax code never materialized, but the tax cut energy animated many of the policy changes over the past half-century. The last section of this blog includes an outline of the significant tax changes between the 1970s and 2010s.

The Estonian Model

The excessive and overwhelming complexity of the US federal tax system has animated the long-running interest in fundamental tax reforms. However, the very complexity that politicians decry makes reform difficult as vested interests in politics and industry benefit from the myriad special interest loopholes. Simple, efficient tax systems are not just the province of theory; they exist in the real world. The European country of Estonia is a good example.

Estonia ranks first on the Tax Foundation’s annual list of most competitive tax systems. Estonia levies a single-tier flat income tax rate of 20 percent, paired with a distributed profits tax on corporate income. A tax on distributed profits is only assessed when business profits are realized through capital gains or dividend payments. This system eliminates the corporate income tax, removes additional taxes at death, and avoids double-taxing business income. The system is so simple that Estonian taxes are typically filed in about five minutes through an online portal.

The Tax Foundation modeled the economic and budgetary impact of applying the Estonian tax system to the United States. Such a reform would be approximately revenue-neutral, grow the long-run size of the economy by 2.5 percent, raise after-tax incomes by 3.5 percent, and reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio by more than 9 percentage points thanks to the larger economy. The reform could also lead to tax compliance costs falling by more than $100 billion annually.

Cato Tax Reform Plan

Big tax reform plans that propose an entirely new tax system to replace the existing system are helpful in setting the goals of reform, but they often obscure the difficult politics of actually doing away with the existing tax code, riddled with popular loopholes and targeted subsidies. The Cato Tax Reform Plan takes the opposite approach, working from the existing tax system to present a list of specific reforms that would be necessary to move the federal income tax to a flat tax with historically low tax rates on business income.

The Cato plan would repeal $1.4 trillion in annual tax loopholes, including energy tax subsidies, corporate research credits, housing tax credits, subsidies for children and work, deductions for mortgages and state and local taxes, exclusions for health insurance, and subsidies for education, among many others.

If Congress entirely eliminated all existing distortionary loopholes, deductions, and credits, it could cut tax rates to near 100-year lows. The plan proposes to:

cut the top marginal income tax rate to 25 percent for workers and small businesses to approximate a flat-tax system;

cut the corporate tax rate to 12 percent, making the United States the most competitive place in the world to do business;

cut the capital gains and dividends tax rate to 15 percent;

allow permanent full expensing for all investments;

create universal savings accounts for nonretirement savings; and

repeal all alternative minimum taxes, additional investment taxes, and the estate tax.

The plan is intended to show that massively pro-growth, fiscally responsible tax reform is only constrained by a political preference for keeping the current level of spending and the trillion dollars of tax subsidies littered through the tax code. The plan is also a comprehensive list of options for tax reform from which less aggressive tax reform plans can be assembled. Congress can and should go further by cutting spending, which would allow deeper tax reductions.

Ultimately, the policy tradeoff is between the tax base and the tax rates. The more loopholes Congress maintains in the tax code, the higher the tax rates must be.

Wealth Taxes: Radical in a Different Way

During the 2020 presidential campaign season, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D‑MA) and Bernie Sanders (I‑VT) proposed wealth taxes, making the policy a central campaign issue. Wealth taxes are neither a feature of income nor consumption taxes, which tax regular economic flows. Instead, wealth taxes are levies on a stock of assets and are intended to be purely redistributive, aiming to reverse a perceived inequality in the distribution of resources. For more on the trends, causes, sources, and benefits of wealth in America, see Chris Edwards and Ryan Bourne’s “Exploring Wealth Inequality.”

Property taxes, such as the ones assessed on your house, are a type of wealth tax, but unlike most other wealth taxes, they don’t subtract liabilities (the mortgage). The United States has the fourth-highest property taxes in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). The estate tax on transfers at death is also a wealth tax.

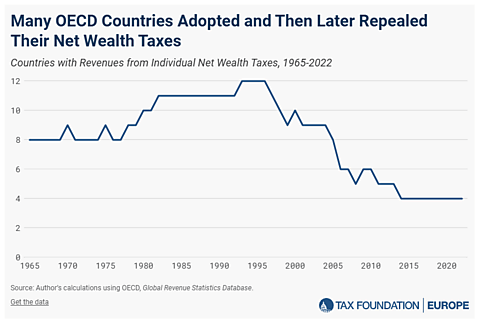

Net wealth taxes have been tested in other countries and repealed due to high economic costs and administrative burdens. Peaking at 12 in the 1990s, only four OECD countries still impose net wealth taxes today: Colombia, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland. The figure below from the Tax Foundation shows the trend of wealth taxes over time.

Wealth taxes impose an additional layer of tax on the income generated by the underlying asset. Most wealth is made up of productive assets, such as active businesses or other investments. The capital gains, dividends, and other income earned would have already been taxed through the normal tax system. One recent Biden-era Treasury study found that the wealthiest 92 Americans faced total state, local, federal, and international income tax rates of 59 percent.

Because wealth taxes are assessed on a stock, expressing the actual tax rate in equivalent income tax rates is more informative. Unless the taxpayer is expected to slowly sell off their underlying assets, the tax will be paid from annual income. The table below shows the equivalent income tax rate on underlying assets with different rates of return at different wealth tax rates. At Sander’s top wealth tax rate of 8 percent, any asset earning less than an 8 percent annual pre-tax return would face income tax rates above 100 percent before paying other taxes.

Such confiscatory tax rates would have myriad negative economic consequences, including disincentivizing entrepreneurship, reducing employment, slowing wage growth, and shrinking domestic output. Wealth taxes also encourage tax planning by highly mobile wealthy individuals who can leave countries with confiscatory tax systems. Before France repealed its net wealth tax in 2018, the government estimated that “some 10,000 people with 35 billion euros worth of assets left in the past 15 years.”

Because of persistent administrative difficulties and taxpayers’ behavioral responses, wealth taxes raise comparatively little revenue. As summarized by Chris Edwards in “Taxing Wealth and Capital Income,” “European wealth taxes typically raised only about 0.2 percent of GDP in revenues. Given the little revenue raised, it is not surprising that they had ‘little effect on wealth distribution,’ as one study noted.”

Significant Tax Changes 1970s–2010s

Revenue Act of 1978: Cut the top effective capital gains rate from 49 percent to 28 percent. A 1979 change relaxed the “prudent man” rule in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, allowing pension funds to allocate more of their portfolios to higher-return investments, like venture capital. These two changes spurred the modern era of start-up investing, as Edwards notes in “How Wealth Fuels Growth.” The 1978 tax cut passed with bipartisan support, with particularly fervent support from Democrats.

Economic Recovery Tax Act (ERTA) of 1981: Reduced the top personal income tax rate from 70 percent to 50 percent, indexed tax brackets for inflation to prevent “bracket creep,” cut capital gains taxes from 28 percent to 20 percent, expanded IRAs, and allowed accelerated depreciation for business investment. The bill was President Ronald Regan’s first tax cut package and, according to estimates from the Tax Foundation, was both the largest tax reduction in US history and one of the most pro-growth changes, boosting projected long-run GDP by 8 percent. More than half of the 1981 tax cut was ultimately undone by legislation in subsequent years.

Tax Reform Act of 1986: Cut the top individual income tax rate from 50 percent to 28 percent, collapsed the 16 individual income brackets to 2 (15 percent and 28 percent), and lowered the corporate income tax rate from 46 percent to 34 percent. The bill was a revenue-neutral tax reform that paired over 100 revenue-raising tax base broadening changes to offset the steep rate cuts. Many base broadeners increased taxes on investment, such as lengthening depreciation schedules, which made the bill mildly anti-growth, according to some estimates.

Deficit-driven tax hikes, 1982–1987: Congress passed a series of tax hikes in the 1980s, including the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, which reversed a third of ERTA’s cuts by increasing corporate taxes and closing loopholes. In 1982, Congress increased the gas tax, increased Social Security payroll taxes in 1983, and included other tax increases in the 1984 Deficit Reduction Act and the 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1990: Breaking his “read my lips, no new taxes” pledge, President George H. W. Bush signed OBRA in 1990, which raised the top personal income tax rate from 28 percent to 31 percent and included other tax increases. The tax increases alienated fiscal conservatives and contributed to the 1994 Republican Revolution.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993: Large tax increases across multiple taxes, including raising the top income tax rate from 31 percent to 39.6 percent, raising the corporate tax rate to 35 percent (from 34 percent), increasing payroll taxes, and raising the gas tax, among other hikes.

Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997: Reduced the capital gains tax rate from 28 percent to 20 percent, created Roth IRAs, introduced a $500 child tax credit, created new education tax subsidies, and moderately increased the estate tax exemption. These tax cuts were a compromise between the Republican majority in Congress and Democratic President Bill Clinton and passed with bipartisan support.

Bush tax cuts (2001–2003): President George W. Bush enacted a series of temporary tax cuts aimed at encouraging investment. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 lowered personal income tax rates, cutting the top rate from 39.6 percent to 35 percent, and doubled the child tax credit to $1,000. The Job Creation and Worker Assistance Act of 2002 introduced a 30 percent bonus depreciation to encourage business investment during the early 2000s recession. This provision was later expanded in the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, which increased bonus depreciation to 50 percent and reduced the top capital gains tax rate from 20 percent to 15 percent and the top dividend tax rate from 38.6 percent (the ordinary income rate, which was being phased down to 35 percent) to 15 percent.

Obama-era tax changes (2008–2012): The Bush tax cuts were extended for two years in 2010 in the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act, which also temporarily reduced the Social Security payroll tax and extended bonus depreciation. In 2012, President Barack Obama signed the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which made some Bush-era middle-class tax cuts permanent but reinstated the top marginal rate at 39.6 percent. Bonus depreciation was only extended through 2014.

As part of the Affordable Care Act, Obama signed into law a number of additional tax increases, including a 3.8 percent surtax on investment income and a 0.9 percent Medicare payroll tax on high-income earners.

The next major tax overhaul came with the enactment of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (and the subject of part two of this series).